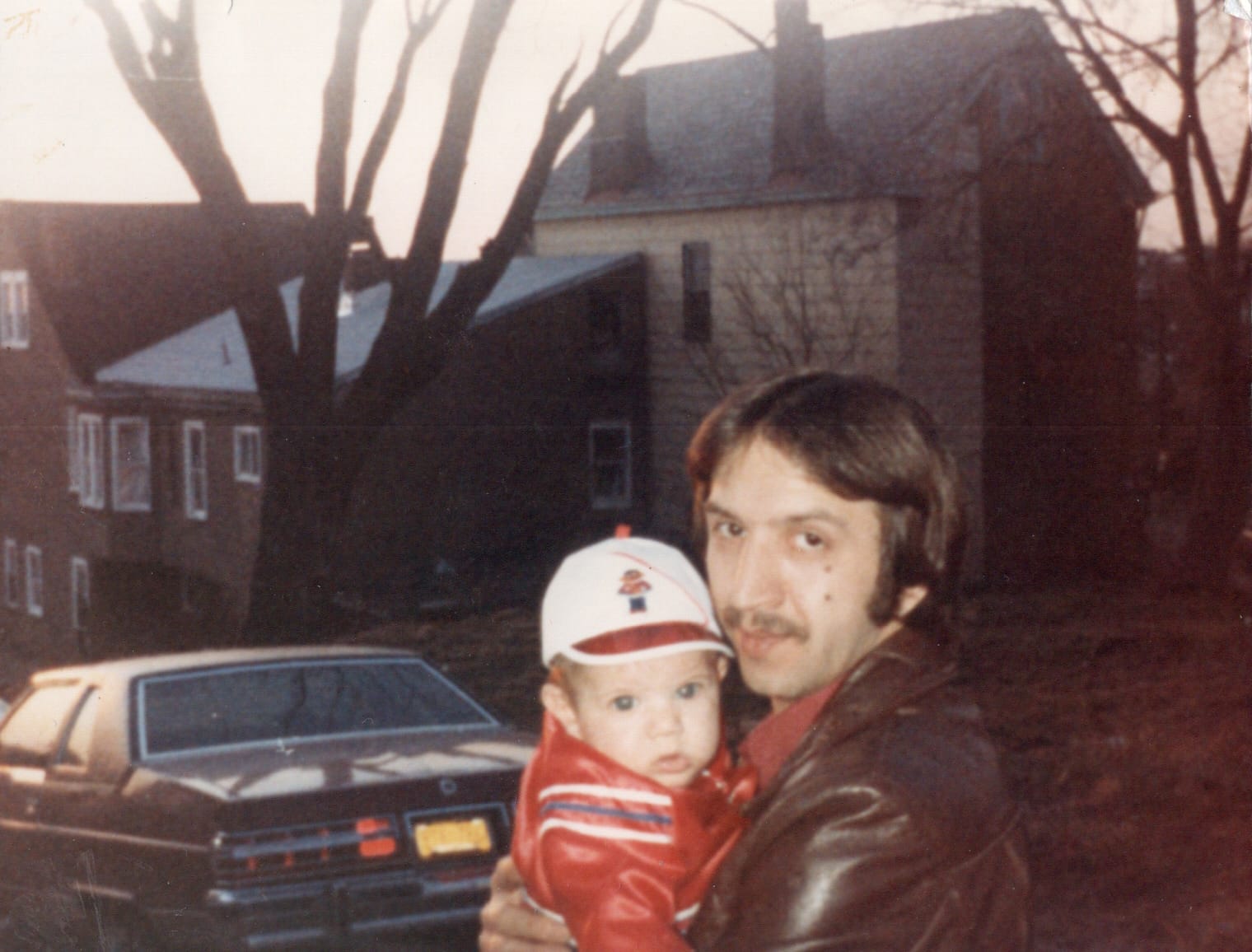

An Undelivered Eulogy for My Father

Because of who he was in life, there was no ritual marking his death. This is my way of saying goodbye.

I’m sitting in a cafe, which is playing songs from Dirty Dancing. Not the cheesy ‘80s tracks, but those excellent ‘60s pop and girl group hits. “Stay.” “Be My Baby.” “Do You Love Me.” Both the movie and its music are part of my firmament. My mom loved both, and growing up the cassette was in heavy rotation in our car. In its way, it soundtracked, along with Prince’s Batman album and Pittsburgh radio station B-94, the well-adjusted part of my childhood — the period of time, roughly 1986-1990, when I was in elementary school, played baseball, and rode bikes with my brother and friends down our street. When “divorce” was something that happened to other people’s parents; when my biggest concern was how quickly I’d get Super Mario Bros. 3.

Nostalgia is something I refuse to wallow in, but I’ve been thinking a lot about that time, and the decade or so that followed, the last few months. A big reason why is my dad, also named Dante Ciampaglia (no middle name), died on November 13. He was 74.

At the end of September, my aunt called to tell me he had stage 3 lung cancer and a brain tumor. My dad and I hadn’t spoken in more than seven years, after a very acrimonious, very public confrontation at my grandfather’s funeral that I knew was the end of our challenging, emotionally abusive relationship. But when I heard he was so sick, I screwed up the courage to call his wife. She was gracious through her pain, putting the phone up to my dad so I could say what I thought was goodbye. He couldn’t speak, and she told me he had a hard time understanding what was happening. A few days later, I called again for his birthday. She put the phone up, again, but this time he responded with these grunts. It’s all he could muster. I’m glad that he could hear me, that he knew I tried to connect with him. And I’m glad that my last memory is that sound and not silence.

I don’t like personal essays. I don’t like reading them, and I don’t like writing them. But my dad didn’t get a funeral, and there was no opportunity to eulogize him or say out loud some of the things I think people need to hear about him, from me, his first born. So, if you’ll indulge me…

Plenty of people find great role models in their parents. Dad was never that. But I learned a lot from him — what not to do, how not to act, who not to be. Seeing and experiencing how not to be is a rare education. I’m a better father for it, a better husband, a better son, a better friend, a better man.

Dad hurt a lot of people, including me, in a lot of ways. He stole. He lied. He cheated. He committed crimes — some of which he was punished for. He burned every bridge, and at the end of his life most everyone was gone. His brother stopped talking to him. He didn’t really have any friends. His three children cut him out of their lives. He didn’t know his grandchildren.

I know there are people rejoicing that someone rotten is gone from the world. I'm not one of them.

Anyone who knows me knows how core my, frankly, fucked up relationship with my dad is to who I am today. I could go on and on about the emotional punishment I suffered as the oldest of three boys forced to be an adult at 8, to carry responsibilities and baggage most grown ups never and couldn't handle. My brothers didn’t have to negotiate the minefields of the brutal trench warfare that was my parents’ divorce, and I bore the brunt of a lot — especially from my dad — so they wouldn’t have to. It's hard to forget the supervised visits; being stood up on your birthday so he could be with a girlfriend; coming back from vacation to find a gift you gave him in the mail with a note that we might never see each other again simply because we went away on one of his weekends; seeing him wearing an ankle bracelet; being told any number of ways — without actually saying it — that everything is my fault. That's a lot to take when you're 9, 10, 11 years old. But it’s fine; I came out OK, thanks mostly to my saint of a mother. Still, the scars are deep and raw. I’m sure I’ll be excavating repressed memories the rest of my life.

In the last couple of months, though, I’ve been thinking about the ways he impacted my life, the ways I didn’t fully appreciate. Like, for example, movies. I always knew my love of baseball came from Dad, and that my collector impulse was stoked buying baseball cards with him. But I never grasped how important he was to the formation of the moviegoer and cinephile I am.

My earliest memory is sitting in a movie theater between my parents, uncomfortably watching Tom Cruise and Kelly McGillis try to eat each other's faces in Top Gun. I would’ve been 4 years old. We had a VCR and a bunch of tapes and HBO, off which we recorded more movies, at a time when all of that stuff was massively expensive. Did he lie, steal, cheat to get them? Maybe. Back then it never crossed my mind — I could watch Raiders of the Lost Ark and Return of the Jedi whenever I wanted. And, post-divorce, we typically went to the movies during our weekends together. I did a rough accounting of what I saw with him from September 1990–December 1998. It’s at least 110 movies, and that's just what I remember from scrolling through release lists on Wikipedia. Add in what we saw before my parents split, and the number grows sharply.

And then there’s this time we were at my grandparents’ house — he lived with his parents until he got remarried — watching The Dirty Dozen on TV. My brother and I loved Victor Franko, played by John Cassavetes, and I remember Dad telling us, “You know, he acted to make money to make his own movies.” I didn’t appreciate just how odd this statement was until I saw the films Cassavetes made. How did my dad, who was not adventurous or intellectual or an art lover, know about Cassavetes the pioneering, independent filmmaker?

When I made this connection between my dad and my love of film and began scrolling those Wikipedia lists, I was overwhelmed with sadness. There was so much pain for so long that it fogged out so much else. I couldn’t know to connect with him on this experience — to appreciate something so positive and meaningful until he was all but gone.

In the days that followed his death, the sadness remained. I'm sad for what I lost. I'm sad for what I never had. I'm sad for what was never possible. But it was joined by a kind of loneliness. Because of who he was in life, there was no ritual marking his death, no wake, no funeral, no nothing. This is the best he's going to get. I heard from some family, and later that week I spent a day with two of my oldest friends, which was a true gift. But mostly I felt, and feel, alone. My dad wasn’t a part of my life for years, but he was at least in the world. Now he’s not. How do I process that and allow grief to exist alongside the painful experience of being his son?

Dad did some unforgivable things to a lot of people, me included. And, as far as I was concerned, his punishment was not having a relationship with me or my daughter. He earned it. But I decided a long time ago that, for my own reasons and peace, I needed to forgive him for what he did to me — and only to me. So I have. It took work; it will continue to take work. And it doesn’t mean I forget what he did, who he was, how he acted. I couldn’t even if I wanted to. But when I think about him, especially now that he’s dead, I would rather return to the shards of positive memories and experiences — images like those I included here — than some deep pool of resentment. I'll always have the scars of emotional trauma to remind me of what I endured. The good is what needs to be tended to. Because, despite everything he put me through, he's my dad. I love him.

I never mentioned Dad to my daughter, but strangely she asked about him for the first time the week I found out he was sick. I tried to explain that I don’t talk to him, that he hurt people, that he hurt her grandma, that he hurt me, but that now he was very sick. The weekend before he died, Raquel and I took Isabella bowling for the first time. Her idea! She had a good time. A few days later, I told Isabella he died and she instinctively knew I would need some help. She’s wise and empathetic beyond her 6 years. As we walked to school, she talked about how much fun she had bowling and how she wanted to go again. I told her that when I was a kid, I loved bowling so much I had my own ball, this light blue thing with my name on it.

“My dad bought it for me,” I told her.

“Could your dad be kind sometimes,” she asked.

“Yeah, Isabella, he could,” I said. “But not often enough.”

Comments ()