Transcripts: Manfred Kirchheimer (in memoriam)

"To me the films are all current, and New York life in them is current. So, I'm sorry to disappoint you but I don't really see what others do."

Documentarians rarely become household names. Errol Morris, Michael Moore, and Morgan Spurlock are a few of the rare exceptions. And even then, two of the three gained notoriety through stunt filmmaking. So it’s no surprise that few took notice when Manfred Kirchheimer died, at age 93, on July 16. Or that it took nearly a month for an obituary to appear. He was an artist whose laurels came late in life; why should the fade out be any different?

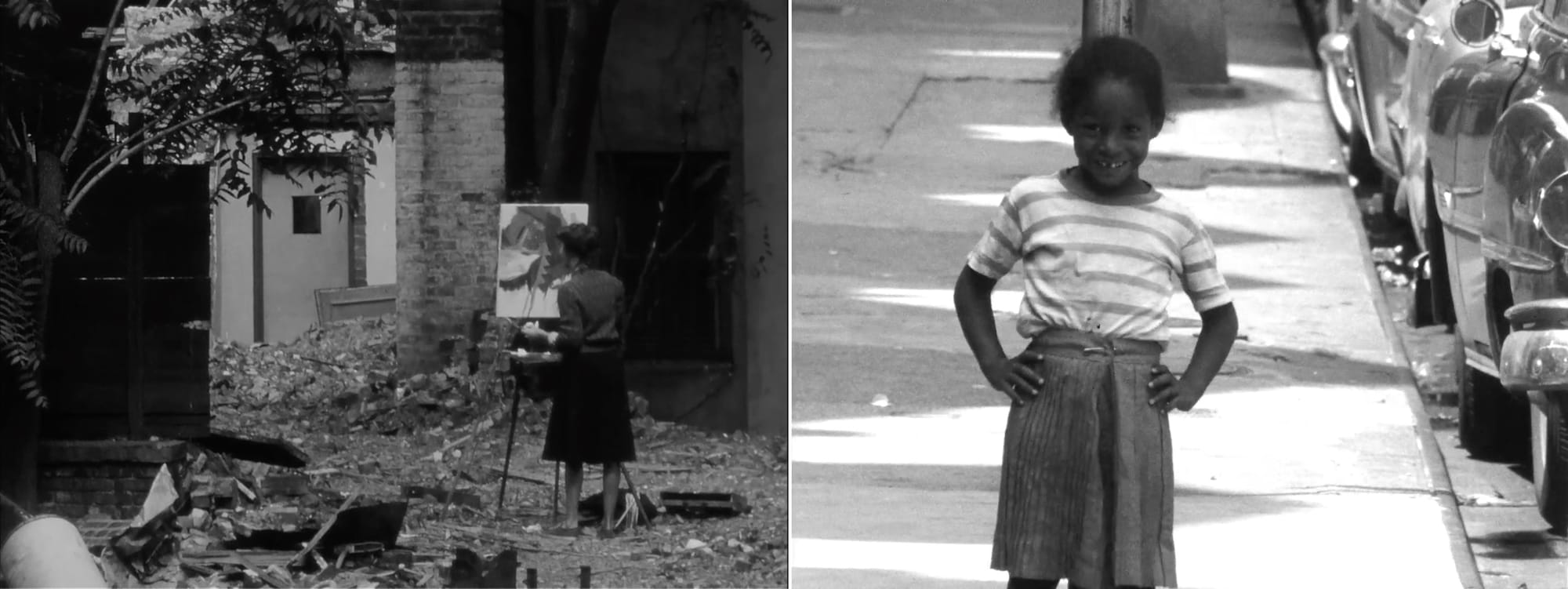

If you know Kirchheimer at all, it’s likely for Stations of the Elevated, a 45-minute poem, released in 1981, glorifying the then-maligned art of graffiti by capturing it in motion, with a Charles Mingus jazz score, as it rumbled by on New York’s subway cars. It’s a proto-hip-hop film, crucial to both the validation and preservation of graffiti as a mode of artistic expression. It’s also a provocation. Footage of the spray-painted subways, renounced by authorities as criminal civic embarrassments, is in tension with shots of gigantic hand-painted billboards promoting empty consumption, erected in the densest parts of the urban jungle with the full approval of politicians and businesses. Which is the actual blight on the urban experience, Kirchheimer asks. Of course, the question is rhetorical. (The original title, per his annotated script, was As Vile as Ever.)

Like other postwar cinema artists such as Helen Levitt, Jonas Mekas, and Morris Engel, Kirchheimer’s films — graceful, populist, empathetic — capture the seemingly mundane and elevate it to mythic status. That’s seen in his first films, like Colossus on the River (1965), about the arrival of a steamship, and Claw (1968), documenting the destruction of an old building for a glassy Modernist tower. It’s there in his later output, particularly Canners (2015), following a couple dozen people around New York as they collect cans and bottles, and My Coffee With Jewish Friends (2017), a simple yet profound document of community conversation. And it’s present in the films he made near the end of his life out of footage he shot as a younger man. Dream of a City (2018) and Free Time (2019) both emerged from material captured between 1957-1960 of everyday New Yorkers — children and the elderly, Black and white, man and woman — doing everyday things like reading the newspaper and playing stickball. The 16mm film he shot with Walter Hess never coalesced into something bigger, but Kirchheimer never forgot the people and their stories, even as he neared the conclusion of his own story.

Kirchheimer was born in 1931 in Saarbrücken, Germany, and arrived in New York in 1936 when his Jewish family fled the Nazis. After studying with legendary Dadaist and experimental filmmaker Hans Richter at City College in the 1950s, Kirchheimer began his career as an editor. It’s no surprise, then, that his documentaries are masterful pieces of assemblage. It was his editor mindset that allowed him to turn long-ago footage into a trilogy of films. (Claw also came out of that ’57-’60 cache.) And it was his instincts as an editor that allowed him to see bigger stories within the people, places, and experiences most of us overlook.

An unintentional effect of his observation was to preserve a key moment in New York’s growth — not just as history but as an expression of solidarity across the decades. Our contemporary New York is visible in that long ago place as it builds toward its future, our present. It’s an outcome Kirchheimer never really accepted, as I found when I interviewed him in 2017 for an Architectural Record piece about his films ahead of a MoMA retrospective. It wasn’t that he disagreed with the assessment, just that it wasn’t his intention. He sounded bemused by it all, if anything.

Kirchheimer was 86 when we spoke on January 25, 2017, and he had the bounce of an artist whose day had finally come. It was an enjoyable conversation with an artist who loved what he did, knew he was good at it, and was giddy that success had finally found him. Stations of the Elevated was utterly dismissed when it was released in 1981; when it was resurrected in 2014, it was hailed as a masterpiece. His shorts from the ‘60s and ‘70s were seen, rightly, as touchstones of cinema verité. He earned a MoMA series. (Stations and his four early shorts are available on an excellent DVD released by Oscilloscope.)

It was a true joy to speak with Kirchheimer. Rather than let the full conversation languish on a hard drive, I thought I’d publish it here. It’s edited slightly for clarity, but otherwise it’s complete, beginning with how he began making films and concluding with what he had cooking in early 2017. It feels like a good way to honor this filmmaker whose work is so good and whose name should be better known.

What made you pick up a camera and start shooting documentaries?

In 1949, I was at City College and there was a protest going on, a school-wide protest against two racist teachers, someone called Davis and someone called Knickerbocker. And I saw a kid with a camera filming it. At the moment he was filming the back of a horse (laughs). And I went over to him and I asked him what was this for, and he said, "Oh, it's for the film institute." And it turned out that there was a film institute, the only documentary institute in the country started by professor Hans Richter, who was a German expatriate, a former Dadaist who now made experimental films, and he ran this school. So, I decided right then and there, since chemistry, which I went in for, really wasn't — the smells alone were enough to (laughs) make me flee the lab — I decided I'd like to try this. My dad prompted me and said, "When you see Professor Richter, ask him whether there are any opportunities in film." So I went into his basement office there at Army Hall, and said, "Professor Richter, are there any opportunities in film?" And he answered, with a heavy German accent, "Yah. Opportunities, there are plenty. But no jobs." (laughs) So that was my start.

I went in for film at City College and I made friends with Professor Richter and I worked for him a little bit after I got out. And then, actually, I didn't pick up a camera for many years. I became a film editor. So let me see... I got out in 1952, and I didn't finish my first film until 1965. I actually did pick up a camera about eight years later, and that film didn't get made, although I took pieces of it and made another film later called Claw. But I made my first film, which was the docking of an ocean liner, I finished that in 1965. And that and the film that I had shot before that hadn't been finished yet was the way I taught myself how to shoot film.

What was it about those subjects that caught your eye?

The first one, the one previous to the first one I finished, was all about New York. It was called Dream of the City and it deplored the new buildings going up and the tearing down of the older buildings. And I still deplore that. It wasn't until the film after the first one, the second film, that I took some of — my partner bowed out and I took some of the material and I made a film called Claw.

My dad was a graphic artist, and he got me excited about everything, about music and museums and art and also architecture. So I discovered Frank Lloyd Wright at a certain point and got all excited about him, even though my dad grew me up on the Bauhaus. I saw how limited the Bauhaus was in its designs, and all these boxes were going up in town and so I was very drawn to that. The ship film, Colossus on the River, the first one I finished, was because, I don't know, I used to go down to the docks and watch the ships come in and out. And so I really didn't have to do much research for it. So that was very attractive. I was living out in Queens and I would take the subway into town at 4 in the morning all by myself with my tripod and camera attached over my shoulder, and so I made that one.

Growing up with all those influences from your father, did you work in any other sort of creative medium before getting into filmmaking?

Well, not really. Once I got into filmmaking, I became the head of the film society at City College and I made posters for them, which my dad approved. I had watched him work over the years, and I got pretty good at graphic arts myself, although in a limited way. But no. I think films is what I did from the beginning.

Did studying with and becoming friends with Hans Richter influence your style? Some of your early work is really abstract and meditative in way that I think some people might not expect from something called a documentary.

You've seen my films?

Yes.

Wow!

(laughs)

Oh. I'm talking to someone who knows my films. Well, that's nice.

I saw Stations of the Elevated when it was BAM a few years ago, and they played Claw with that.

That's right.

Stations of the Elevated is one of those movies that people kept talking about as a graffiti movie, but it really caught me off guard by how poetic it is.

Oh. How nice of you to say. Well, let's see, your question was... Oh! Yes, influences. Well, you know, he influenced me in a way that wasn't like him. He influenced in the sense that one could put together pictures that didn't depend on dialogue. I began to make films at a time when there was a shift to what was called cinema verité, or direct cinema. And I wasn't ready for it. I wanted to do the old stuff because I thought the old stuff wasn't finished yet. There weren't many of us who did that, but some of them... I hooked up with Leo Hurwitz, who became a much more important influence than Hans Richter, and also Sidney Meyers, and these were people who made real movies, you know? They didn't depend on sound or on improvisation. They made, what I call, real movies.

So the influences were really from the '20s and '30s and early '40s, along with the fact that Richter made films in which the sound was always put on afterwards. I wasn't interested in experiment so much as I was in making decent presentations without dialogue. Even though my first finished film, the ship film, has a narration above it. Now, narrations at the time were looked down upon because films you saw in school and educational films and films of that kind always had a narration and it was boring. And when I grew up in films in the '50s, most documentaries still had narrations although, you know, in 1952 when the first cinema verité, so called, films were made, that changed. But until then, the films that were my models were all films in which there was a narration, or no narration but not synchronous dialogue. That was a late comer. So I tried to make films also either with narration or with no dialogue. It wasn't until 1980 that I made my first film with synchronous dialogue, and that's We Were So Beloved, about the German refugees, Nazi refugees.

You said that you didn't feel like you were ready for that verité style. When you go to make something like Stations of the Elevated, how do you determine that this is the treatment that that movie needed?

Aha, well, I came upon graffiti on the trains when I was part of a food co-op. Every month they would choose me and my car to go to the Bronx, to Hunt's Point, pickup fruits and veggies, and bring them back to the Upper West Side. In the summertime, when it was bright out at that hour, I would see these trains go by on the 304 overpasses on the Bronx Expressway. And it was beautiful. Sun was shining on these trains, you saw all 10 cars of them go by from the outside, and I said, "You know, I gotta make a film about that." But of course, at that time, I was just thinking of the graphic notion of them because they were so different from what happened when you were in an indoor platform. I'm at 103rd Street, you know, you go to the platform, you want to find a seat. But this train comes in with this very in-your-face graffiti, you only see a small portion of it, and everybody's grumbling about it, and it looks dirtier than it is because you're indoors. And here I was seeing it in a different mode.

So I decided, also for exposure reasons because it was made on film, to shoot the film outdoors. The first thing I did was buy a book. It was a train book that was out at the time that described all the routes and all the best outdoor-going trains, and I went on all of them, the front car, which, at that time, had a window. And I went to all the ones that went outdoors in order to see where good perches would be for me to shoot from. Then I wrote a kind of a... Now it seems poetic, but I thought it was an outline, a treatment, in which I put down categories and every visual I could summon up for that category. I made one page of these categories, which was sort of the structure of the film and using these lines as headlines I made other pages in which I thought of all the visuals that they could go under. And it turned out that that was my script. I didn't realize it while I was making it, but I couldn't improve on it in script form. So I used that when I went out to shoot, and I had with me always two, sometimes three, students. I was teaching film out at New York Institute of Technology at Old Westbury at the time, and I had very devoted students. I loved them, they liked me. So, I went out and I shot for about three weeks.

Do you remember what some of the categories that were in the script?

Oh, wait a minute. Wait a minute. Can I get the script?

Oh sure, yeah.

You got a moment?

I have as long as you have.

OK, one minute. <goes to get script, a minute and six seconds later...> Well I couldn't find the version I was looking for, but... OK, here it is. Film treatment. So the opening page, I'll read you the outline of the contents:

A gray world (in colored form). There are implications, disturbing but ignored. A train invades. Is rude and not ignored, hated. The train cajoles (cons). Wins grudging interest. Takes us along to see what's behind the implications. What's behind itself. Upsets us, entertains as it stirs us into awareness of atrocity. What reality is sometimes. Threaten others who fear and exposure and reaction. They understand the danger.

And so on. I'm not going to read you the whole thing unless you want me to. But that was about little less than half a page. I used every one of these sentences for... In other words, "A gray world (in colored form)," and I would have a bunch of visuals under it based on my live research. And so on. And so... Yeah. Like that.

There’s an entry in the Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film about your work, and it says that the subjects you choose "create a frame for the larger understanding of city life." You've talked a little bit already about New York City, but I wonder if that was something you had or have as a goal in your movies.

You know, actually not. This came, these words in that encyclopedia and things people have been saying now that there's a resurrection of Stations of the Elevated, are all about that, about my documenting the city, in a way. And I never thought of that. I thought of these individual subjects. I chose the city because it was there and I didn't have the money to go out of town, except on one film, Tall, about Louis Sullivan. I needed to go to Chicago. And to Buffalo. I did get a grant for it. I only got a grant for two of my films. The rest I paid out of my own savings.

What was the other film you got a grant for?

Um... Oh. No, actually... Wait a minute, three films. I got a $10,000 grant for Stations of the Elevated. I got a $70,000 grant for We Were So Beloved. And I got I think $10,000 for Tall. I think. I'm not sure of that.

So, anyway, to answer your question about the city, I think without my knowing it, the city, or partially part of the city, got documented by virtue of the films I made. But the films I made were really very different. I mean, Claw is very different from Stations. And yet they serve, in terms of getting to know the city, a similar purpose. Bridge High is about crossing a suspension bridge. Tall, which features New York and Chicago, has... I don't know. It's a lot about New York. And then my most recent film, which is going to have its premiere at the retrospective, is Canners. Well, my next to most recent film, Canners, which is about people who collect cans for nickels and dimes.

How did you find the subjects in Canners, and how did you get them to talk to you the way you did? They're so open with you.

I know! Isn't that amazing?

It is, especially New Yorkers in 2011 or 2012 or whenever you shot the movie. My experience is, you walk around town and people are now very aware of people with cameras and they almost kind of recoil.

Right. Well, what I did... First of all, I think it's my age. I'm 86. I was 83 at the time. So I think that's one thing. But the other thing is the way I'd approach a canner is I'd stick out my hand. I'd say, "Hey, how are you?" They were almost ashamed to give me their hands back because they'd say, "Oh, my hands are dirty," or they'd take off their gloves and they'd shake my hand. And I think that formed an immediate trust. And then, you know, anything went. It was amazing.

I had my own categories that I wanted to talk to them about in my head. I had them written down somewhere, but I didn't take that along. They talked about everything. It was amazing to me. But, as I say, I didn't really know them. And as we looked for them, we found them by stopping on every block and listening. And if we heard some clinking of glass, we went in that direction. From the Internet, I had gotten a schedule of when the Sanitation Department pickup days were, which meant that that was the day, or the day before, that these workers in buildings put out the cans and bottles. They collect them all week long, and then one day — like in my building it's Monday — they put them all on the sidewalk for a Tuesday morning pickup. So I would only go to those areas in my neighborhood, between 110th all the way to Wall Street, on the days that they were being collected so I knew I'd find one or two people a day. And that's all I needed, you know? If I found two people a day who would talk to me, I'd be happy because, after 11 days, I'd have 22 people, which was plenty for the film.

Did you ever approach anybody that just said, "Get away from me, I don't want to talk to you"?

No, but there were two people that wanted money and I wouldn't give it. And there was one person who just nodded "no." But everybody else was amenable.

You said that you didn't really think too much about how you were documenting New York or that wasn't a goal. But now that people are talking about and looking at your work that way, what do you think your films say about New York or, maybe, life in the city?

I don't know. I really don't know. I know that things have changed. But to me, I find Stations of the Elevated, for example, very current. I find Claw very current. Since I lived with those incremental changes, I didn't... It's like when you have a son growing up or... You don't see it from day to day. And so, as I say, I didn't really think of documenting New York. And now that I'm told that I did, I don't... I don't see it, especially. To me the films are all current, and New York life in them is current. So, I'm sorry to disappoint you but I don't really see what others do.

(laughs) That’s OK. I think there’s this sense in New York that it's always evolving, yet the things in your films that would maybe be historic or historical in shot in other places feel as potent now, here, as they might have then because a lot of the issues that you captured we're still living with.

I made a sequence back in, oh gosh, 1963? Yeah. I made a sequence at that time, which... I finished Claw in 1968, I think. Tt was meant to be for that larger film, but it didn't make it into Claw, which is only a half hour. This five-minute sequence was kind of a machine gun, rat-a-tat of editing. It was unlike other things I've edited. It made its way into Tall, many, many years later, untouched. Cut down a little, OK, but otherwise, untouched. And... I don't know. That was, let's see, Tall was 2004. So that's a modern film, and I don't think anybody noticed that that material was more old fashioned. So, I was able to slip that in.

Do you think that says more about the sort of world we live in or about your work as a filmmaker?

Well, look, let's take Claw. It's about the ruination of the old city and the taking over of the new. And its protagonists are stone figurines, right? Now, if you look at today's city, all there is is more boxes, more glass buildings, more of the same. So it hasn't really changed, except some forms are different than others and it's a little looser now in terms of boxes than it was in 1968. But it’s gotten even denser, but of course we expected that in the early '60s. So in that sense, Claw hasn't changed at all. I mean, the kids who are making love on the stoop, alright, their clothing has changed. True enough. Although I try in the film to shoot above the car line so that you don't identify the time. But it hasn't really changed, that film. And I don't see, except for the fact that there are no more graffiti trains, I don't see that the stations in New York have changed, except for those trains themselves. Everything surrounding them strikes me as the same. There are fewer hand-painted billboards nowadays. But there still are some.

Do current events influence your work in any way?

Not really. That is, when you think of documentaries that are coming out, they're very current. They have to do with, I don't know what... What you read about. Mining alternative electricity... I don't know. They're very specifically about current news, and I think that's a good idea. But somehow I'm not of the temperament to chase it down. And so I make films that aren't really connected to what's going on, except in a larger sense.

For example, Coffee With Jewish Friends, it's all about how people feel about Jewishness. Well, that's not really a big current subject. You know? Before that, Canners. I mean, Canners is not a big current subject. These people are all around you and you tend not to look at them. But it's not an earth-shaking subject. I don't know. I come up with things that are dear to my heart, but I don't really chase down current stories.

It's interesting you say that about Canners because it feels like, you hear some of the stories of the people you talk to and it sounds like they either got into it or committed more to it after the recession or after Hurricane Katrina, these sort of economic catastrophes.

Yes. That's true. But I didn't count on that when I started. These were surprises to me. I mean, I went in there without any prenotions. I made a little pre-film before I made this film, a half-hour film with a little point and shoot camera, just to see if I could do it. And I was surprised at how open people were with me. And then I got my crew together and we really shot the film. But things that people said... I don't know. They came out of the blue for me. I was surprised by them. And that's true of the Jewish film. People say things, talk about things, that I didn't imagine they would. I'm very grateful for it. It makes it fresh. But I don't plan it. I just plan to be as open as possible.

It feels like since Stations of the Elevated was rediscovered a few years ago, there's been more interest in your work. What was your reaction when people started to say they wanted to come talk to you about your work, to show your films?

Oh, I was very excited. I mean, nothing much had happened. I just kept making films. And I got this call from a guy called Jake Perlin who said that he got my number through the Lincoln Center film library. And what's the status of Stations of the Elevated? He saw it 10 years ago and he fell in love with it and he's always wanted to do something with it. I said, you can have it, except that I don't have the music rights. And he said, "Well, what does that involve?" I said, "Last I heard, it was like $16-20,000." He said, "Oh, that shouldn't be a problem." So, eventually after about a year, he got the rights to the music, which is Mingus and Aretha, for around $30,000. And I worked it off on royalties. I mean, he negotiated it, he paid for it. And he's become my agent. And, you know, he arranged for the BAM thing. He arranged for the Harvey Theater, the big showing they did in the 850-seat theater. I don't know if that's where you were. And he has been instrumental in getting me this MoMA retrospective. And then, a month after the MoMA retrospective he's going to... He now runs Metrograph, Jake does, and he's going to open Canners there on March 10 for a week. He's been my guardian agent. (laughs) So that's what happened to me, suddenly, three years ago. And I'm very excited about being interviewed and stuff like that. Didn't used to happen.

How do you feel about the MoMA retrospective and having all, or so much of, your work shown?

Yeah, it's all of my work, really. And I'm thrilled by it, I really am. That they should have taken me up, you know... They're throwing a cocktail party for me that night, the first night, I'm really thrilled by all the attention they're giving the films. They're showing every film twice. What can I say? I hope the films are deserving.

Comments ()